Decorated Cribbage Board

Decorated on One Side with a Dog Sled and a Totem Pole; on the Other Side with a Landscape of the Mountains and Sea Ice

Hood Museum of Art | 8 1/8 × 1 9/16 × 11/16 in | Gift of Warren Prosser Smith, Class of 1913

Cribbage, Caldwell, and Questions

Manufacturing Art, Recreation, Dominance, Resistance, and Tradition through the Ivory Cribbage Board

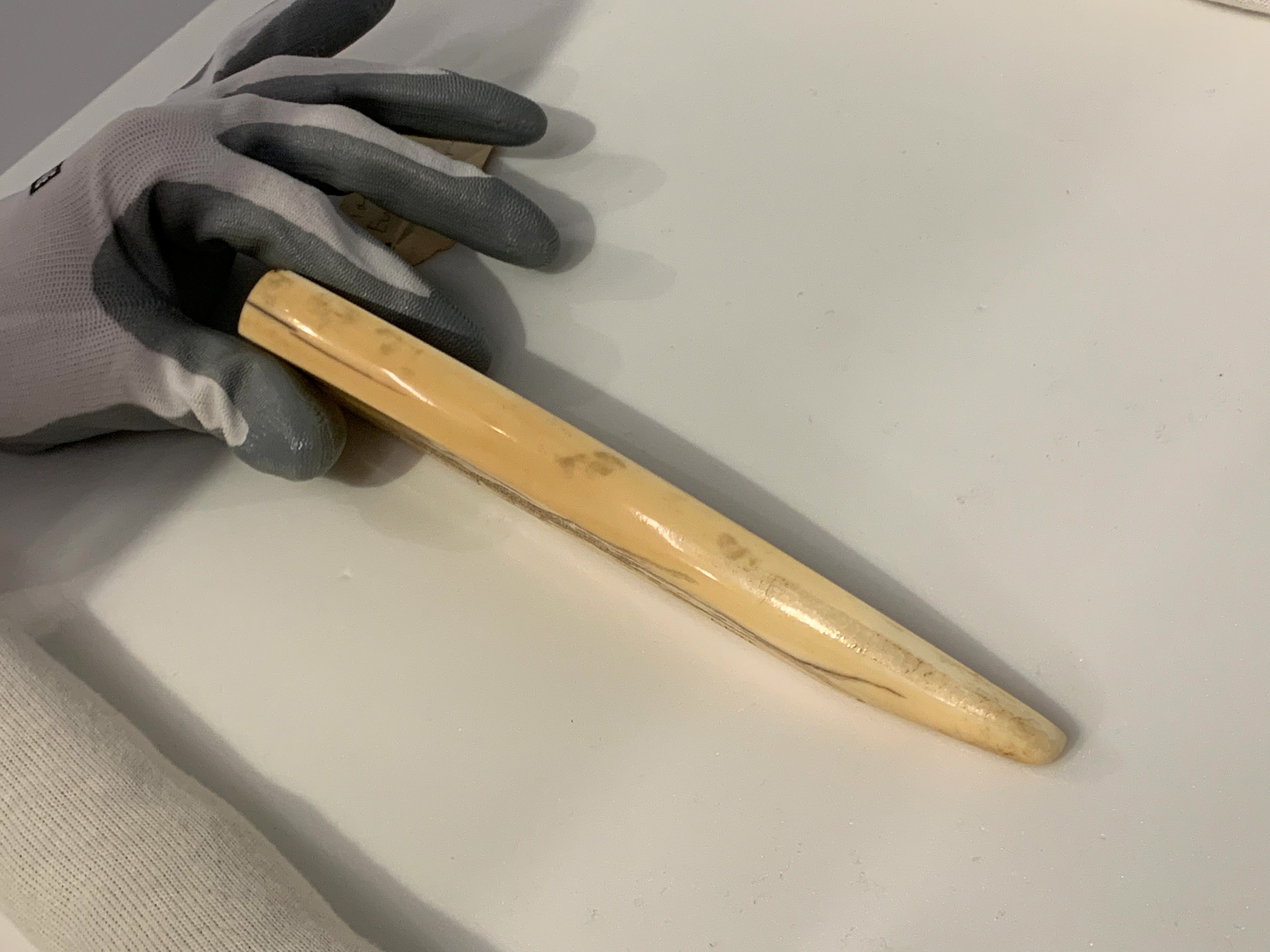

The museum curator, balancing this ivory cribbage board in her gloved hand, estimates that it weighs about twice as much as her iPhone. A Google search reveals that this is about half a pound – surprisingly hefty for a fang-like object only slightly longer than a pencil. Surprising, too, are the scratches running along its sides and the two long cracks incorporated into the mountainous horizon etched into its surface. But scan your eyes along the sides of the board, and you will note smudges of darker, grayer bone where its owner has touched it, retrieved it from a shelf, placed it on a dining room table, and dealt two hands of cards, over and over. Ivory darkens to the touch, splinters in low humidity (Museum Conservation Institute 2022); this object was used, loved, and worn down before joining the collection, courtesy of Warren Prosser Smith, a member of the Dartmouth College Class of 1913, and his daughter (Hood Museum of Art 2022). How often did they play? How treasured was this board?

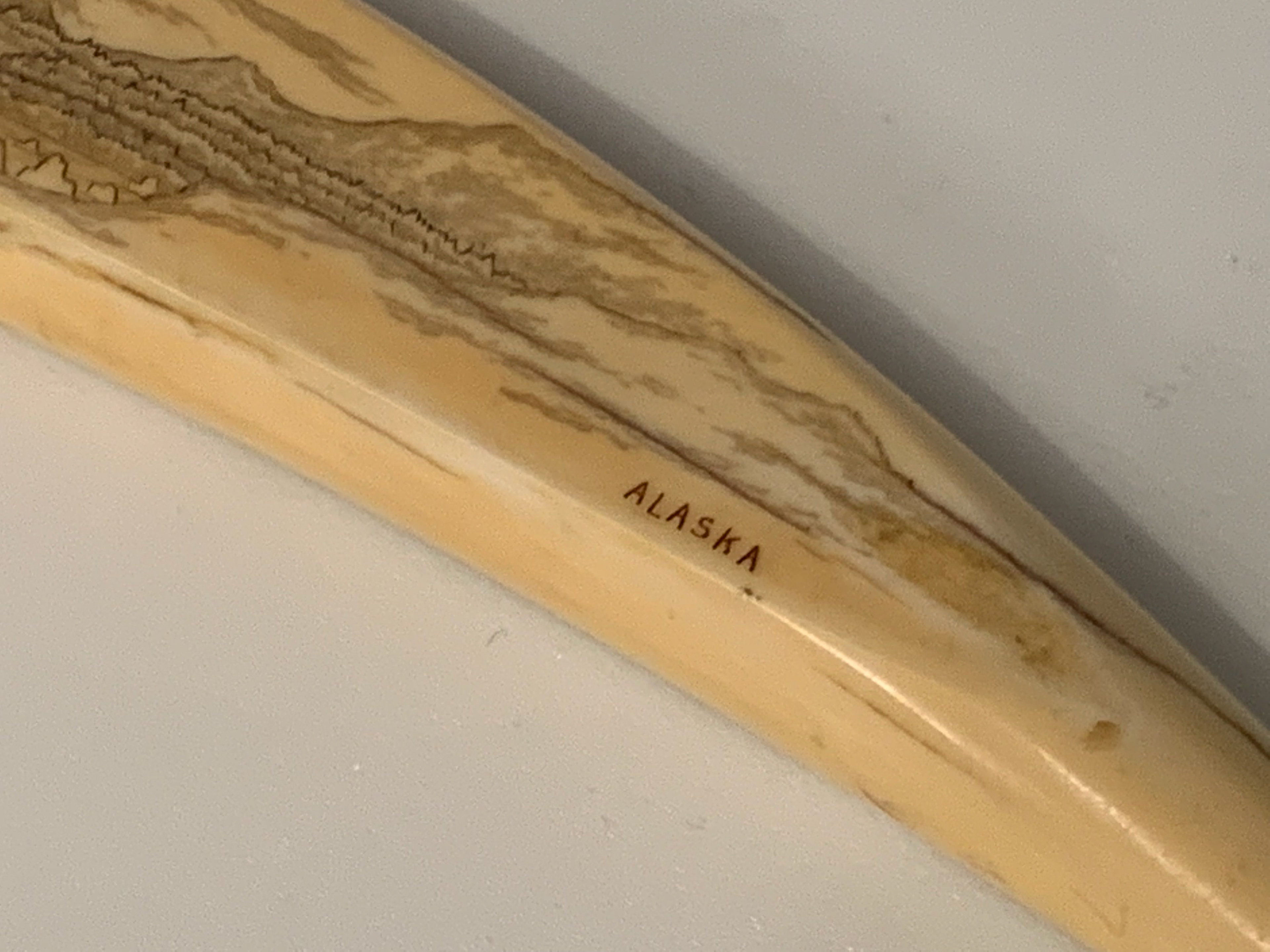

Inscribed on the back of the object is an icy bay, ringed by snow-capped mountains; at the bottom of this scene, etched in bold lettering, the word “ALASKA” broadly locates the scene. Lurking beneath these waters might lie a huddle of walruses like the one from which this tusk was taken, sawn in half, sanded smooth, incised by skilled hands. On the other side of the board are the 12 rectangles, each containing ten peg holes, needed to count the 121 points that constitute a winning round of cribbage. Beginning at the wide end of the flattened tusk, sweeping together across its surface, and encircling an inscribed totem pole, they meet near the board’s rounded point. There, they encroach on a snowy landscape etched into the bone, each light divot lined with brown, fading ink; the straightened, imperial rows layer themselves atop the more unwieldy lines forming themselves into an image of a dogsled team bursting through the treeline. The object’s provenance proves equally layered.

Gifted to Smith by his uncle, Caldwell W. Tuttle, the board was “made for sale,” according to the searchable tags lining the tusk’s Hood Museum of Art webpage. Commissioner of Sitka, Alaska, from 1897 to 1900, Tuttle likely purchased the souvenir tusk, a newly popular item, from one of the several curio trading shops springing up in the area, from a local artisan, or from a trading ship moored near Old Sitka Dock, in the town’s seaport (Ray 1969, 128).

It is listed as one of four such boards, each made of walrus ivory, held by the museum. The artist, while unknown, was likely a Native Alaskan person working in the mid-19th century, the site notes. When viewed in person, though, a worn tag, attached with twine to the knob protruding from the board, contends, in scrawled pencil, that it was “Made by European (S. Kaplan).” It is the only board included in the Hood Museum’s collection not to be attributed to the Iñupiaq or Yup’ik tribes in Western Alaska.

Ivory cribbage boards first appear in the historical record in the 1890s, emblematic of a burgeoning tourism trade spurred by an influx of adventurous, gambling gold-seekers (Hollowell-Zimmer 2002). Typically inscribed with Alaskan Native imagery, these objects forgo traditional etching styles for more western pictoralization (Ray 1969, 16). Reaching their zenith in a period when white collectors sought Alaskan Native artifacts of all sorts as specimens for anthropological inquiry, as trophies of the new colonial project, and as some combination of both, similar boards appear in the collections of museums as far-ranging as the Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, the British Museum, and the National Museum of the American Indian (Engelhard 2018, 48). They are even sold today as collectible artifacts of Alaskan Native artisanship in stereotype-reinforcing “trading posts” in states that allow the sale of antique ivory.

Thus, these boards constitute multifaceted sites of artisanal skill, commercial value, collectible wonder, and social ordering, both in the time of their creation and in their continued prevalence, leaving their observers with questions:

How did so many segments of valuable tusks come to be inscribed with both the markings needed to play cribbage, a game originating in Britain, and with imagery of totem poles, central objects in Tlingit and Haida culture? To what degree is this blending of animalia, Indigenous craftsmanship, and settler material culture a reflection of or an agent in the building of a new social hierarchy in Alaska at the time? Should the sudden shift in engraving style, new use of ivory, and new sale of objects by Indigenous artisans in the late 19th century be read as an imposition of colonial power or these artisans’ creative reaction to a changing economic structure and demand for “authentic” Native artifacts?

For this board in particular, how does a carved tusk, likely taken from a walrus in the Bering Strait, come into the hands of a government official in Southwestern Alaska (Alaska Department of Fish and Game 2022)? How did this skillful work come to be attributed both to Native and non-Native makers, and why would each have an interest in crafting it? How does this board, created as a souvenir for frustrated gold-hunters, simultaneously constitute an exciting gift for a young student on the East Coast and a meaningful donation to a growing college museum?

For answers, this digital exhibition turns to the historical context of 1890s Alaska, the smooth wooden pegs of a traditional Tlingit game, the frowning face of an ivory Haida figurine, the more recent collection of “Alaskan Eskimo” yo-yos, the walrus remains from which ivory is culled, the early etching style inscribed in an Iñupiat bow drill, and the continued collection of ivory cribbage boards.

REFERENCES

Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “Pacific Walrus (Odobenus Rosmarus Divergens): Species Profile.” The Great State of Alaska Fish and Game. Retrieved May 29, 2022: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=walrus.main

Engelhard, Michael. "Working the Ocean's White Gold." Alaska, 10, 2018: 48-49. https://www.proquest.com/magazines/working-oceans-white-gold/docview/2112526494/se-2?accountid=10422.

Hollowell-Zimmer, Julie. “THE LEGAL MARKET IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIALS FROM ALASKA’S BERING STRAIT.” Revista de Arqueología Americana, no. 21., 2002: 7–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27768458.

Hood Museum of Art. “DECORATED CRIBBAGE BOARD, DECORATED ON ONE SIDE WITH A DOG SLED AND A TOTEM POLE; ON THE OTHER SIDE WITH A LANDSCAPE OF THE MOUNTAINS AND SEA ICE.” Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College. Retrieved May 26, 2022: https://hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu/objects/169.30.2470

Museum Conservation Institute. “The Care and Handling of Ivory Objects.” Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute. Retrieved May 28, 2022: https://www.si.edu/mci/english/learn_more/taking_care/ivory.html

Ray, Dorothy Jean. Graphic Arts of the Alaskan Eskimo. District of Columbia: U.S. Indian Arts and Crafts Board; U.S. Government Printing Office, 1969.