Historical Context: Colonizing, Collecting, and Creating in Sitka

Sitka, Alaska | 1741 - 1900

Image Credit (for all on this page): University of Washington Digital Collection

Sitka is nestled between snow-capped mountains in Southeastern Alaska on the narrow strip of coastal land closest to Canada. Home to the Tlingit and bordered to the south by lands inhabited by the Haida, the city’s population is 17% Alaskan Native today (City and Boroguh of Sitka, Alaska 2022).

Sitka’s harbor first housed settler ships in 1741, during the first Russian expedition to Alaska (Tikkanen 2012). Russian colonization was centered out of this Sitka settlement, the headquarters of the Russian-American Trading company and the location of Fort St. Michael, a recently rediscovered military base built on a bluff overlooking the port. Relations between the Tlingit and the Russian colonizers were violently contentious, boiling over in 1802 with the destruction of this fort by members of the Kiks.ádi clan of the Tlingit and again in 1804 with the deadly, retaliatory attack led by a Russian navy captain.

Upon Secretary of State Seward’s $7 million purchase of Alaskan land, including unceded Tlingit and Haida land in and around Sitka, the city hosted the 1867 ceremonial transfer of power and became the functional seat of the new American territorial government (Gannon 2021). Enforcing military rule, the United States was no less brutal in its colonization efforts: for instance, in 1882, the American Navy bombarded the nearby, small village of Angoon after its Tlingit inhabitants supplied too few finely woven blankets in tribute, destroying most of its buildings and killing several Indigenous people (Furlow 2010).

While mid-19th-century Russian and American settlements of Alaskan land were small, the discovery of gold nuggets along the beaches and creeks of coastal towns prompted a monumental influx of white settlers in the century’s last decade. Stripping the coastline of rocks and stealing its hitherto buried riches, tens of thousands of colonizers swelled towards sifting sites via the White Pass Trail. Following the trail from Seattle through Sitka and up to the western settlements, these travelers constituted the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896 and the Nome Gold Rush of 1899 (National Park Service 2021; Smithsonian Institution 2022).

It is in the midst of both this strong-armed colonization effort and this gold-crazed population boom that Commissioner Caldwell W. Tuttle arrived in Sitka, 15 years after the shelling of Angoon. Newspapers from the time period, including the Stikeen Journal, list Tuttle as one of the officers of the “District Government'' of Alaska (Stikeen River Journal 1899). A document listing the governmental officials on the federal payroll notes that his annual salary amounted to $1,000 (Department of the Interior 1897).

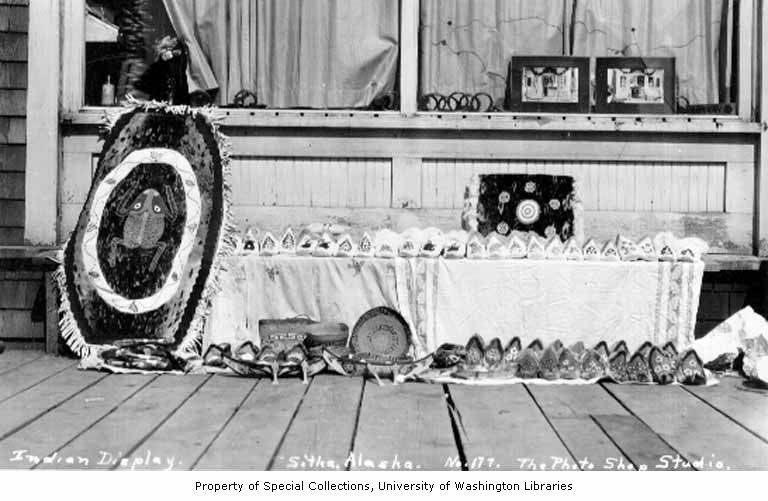

These newspapers also hint at the cultural trends taking root as settlements of white governmental officials, gold-hunters, and other colonizers grew in earnest. Organized cribbage competitions and the sale of “Indian souvenirs” dominate the local pages of these papers, with headlines such as “Good Prizes for Cribbage Contest” frequently listed alongside advertisements for trading posts; declares one, “THE IGLOO is headquarters for… Rare Arctic Curios” (The Daily Alaskan 1905; Nome Semi-Weekly Nugget 1904). At the same time, degrading and racist descriptions of Alaskan Natives pervade these bulletins; take, for instance, an article in which Commissioner Tuttle expresses his doubts that Indigenous people in Sitka will not harm the foreign traders introducing reindeer as livestock in the area (Sitkeen River Journal 1898).

As sources of gold were quickly depleted and frustrated prospectors began to fear returning east or writing home with nothing to show for their plunderous adventures, a bustling souvenir market emerged. White settlers’ fascination with Alaskan Native materials resulted in a booming ivory trade; ivory exports from the Alaskan territory in Tuttle’s first year as Commissioner amounted to 1,000 pounds, according to government documents from 1897 (Tuttle 1897).

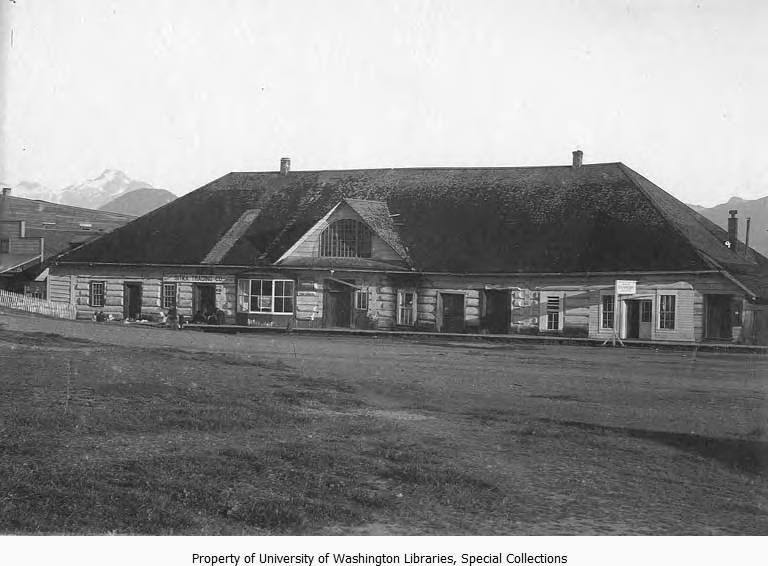

Trading posts, like the Sitka Trading Company warehouse pictured below, sprung up to facilitate the massive, concerted shipment of natural and anthropological materials, both “authentic” and made-to-order, to curio shops, museums, and a curious American public on the east coast. Simultaneously meeting the colonial demand for anthropologically intriguing and precious Alaskan Native artifacts fashioned from ivory and the recreational demand for cribbage boards (that could, usefully, publicly denote status when used in public gambling competitions), these trading posts actively encouraged the creation of walrus tusk cribbage boards (Hollowell-Zimmer, 20). It is in this material cultural climate that Commissioner Tuttle purchased the “Decorated Ivory Cribbage” board held by the Hood Museum of Art; by the time he gave it to his nephew, there were thousands like it.

But if white settlers in Sitka were so fascinated by and interested in collecting emblems of Tlingit and Haida culture, why is the most popular collectible souvenir from this period an ivory cribbage board – reflective neither of traditional Alaskan Native recreation nor ivory usage? Is this an instance of colonial power-brokering (a declaration that Indigenous artisans must now make materials for use by white settlers) or an act of hidden Indigenous resistance (an economic project in which Alaskan Native artisans use their unique skills to creatively take advantage of the white settlers’ obsession with both Indigenous artifacts and ivory)?

Sitka Trading Company, Sitka, Alaska, between 1900 and 1915.

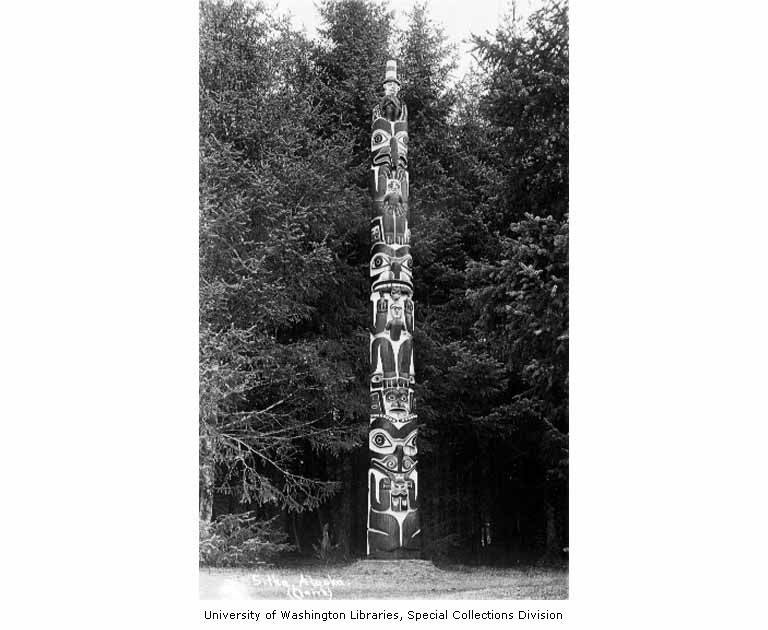

Haida totem pole, Sitka, Alaska, between 1900 and 1938.

Display of Alaska Native crafts and works of art on wooden sidewalk.

REFERENCES

City and Borough of Sitka, Alaska. “About Sitka.” City and Borough of Sitka, Alaska. Retrieved May 26, 2022: https://www.cityofsitka.com/about-sitka

Department of the Interior. Official Register of the United States: Containing a List of Officers and Employés in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service. United States: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1897.

Furlow, Nancy Jean. "Balancing Values: Re-Viewing the 1882 Bombardment of Angoon Alaska from a Tlingit Religious and Cultural Perspective." University of California, Santa Barbara, 2010: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/balancing-values-re-viewing-1882-bombardment/docview/815732539/se-2?accountid=10422.

Gannon, Megan. “Archaeologists Identify Famed Fort Where Indigenous Tlingits Fought Russian Forces.” Smithsonian Magazine. January 25, 2021: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/archaeologists-identify-famed-fort-where-indigenous-tlingits-fought-russian-forces-180976818/

Hollowell-Zimmer, Julie. “THE LEGAL MARKET IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIALS FROM ALASKA’S BERING STRAIT.” Revista de Arqueología Americana, no. 21 (2002): 7–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27768458.

National Park Service. “What was the Klondike Gold Rush?” National Historic Park Alaska. December 16, 2021” https://www.nps.gov/klgo/learn/goldrush.htm

Smithsonian Institution. “The Great Nome Gold Rush.” National Postal Museum. Retrieved May 30, 2022: https://www.nps.gov/klgo/learn/goldrush.htm

Stikeen River Journal. (Fort Wrangell, Alaska). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. September 24, 1898: <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94050095/1898-09-24/ed-1/seq-2/>

Stikeen River Journal (Fort Wrangell, Alaska). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. February 4, 1899: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn94050095/1899-02-04/ed-1/seq-3/>

The Daily Alaskan (Skagway, Alaska). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. November 24, 1905: <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014189/1905-11-24/ed-1/seq-3/>

The Nome Semi-Weekly Nugget (Nome, Alaska). Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. July 9, 1904: <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2018270501/1904-07-09/ed-1/seq-2/>

Tikkanen, Amy. “Sitka, Alaska, United States.” Encyclopedia Britannica. June 28, 2012: https://www.britannica.com/place/Sitka.

Tuttle, Charles Richard. The Golden North: A Vast Country of Inexhaustible Gold Fields, and a Land of Illimitable Cereal and Stock Raising Capabilities. United States: Rand, McNally & Company, 1897.